Despite the strong prejudices in the United States against Chinese immigrants in the mid-to-late 19th century, some Chinese were still willing to serve the country by joining the Army. Chinese fought in the Civil War for both the North and for the South. The National Park Service publication in 2015 is an excellent book about Asian and Pacific Islanders who served during the Civil War. Joseph Pierce, Edward Day Cohota, and Thomas Sylvanus were among the men described in detail in the book.

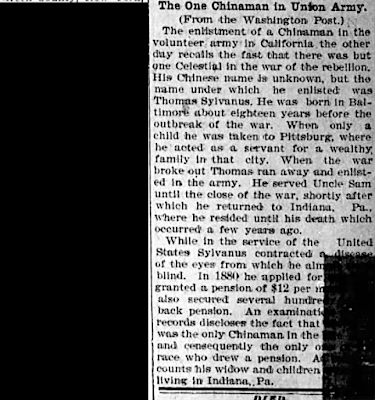

Thomas Sylvanus, born in Baltimore, was thought to be the first Chinese to fight for the Union Army.

After the war, they continued to face anti-Chinese feelings, physical attacks, destruction of Chinatowns, and even being run out of town. The government’s promise that those who served in the war would receive citizenship was unfulfilled, so they couldn’t vote and ineligible for homesteading.

Hostile attitudes toward Chinese in the Army continued a generation later as attested by newspaper articles from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of WWI. When a “Chinaman” joined the Army, it made “news." Newspaper articles went beyond providing information about any Chinaman joining the Army but often made fun of them. In 1899, when Craig Tow, a Chinaman born in the U.S. enlisted, the newspaper article pointed out that he cut off his queue before joining the Army.

One egregious article in 1917 reporting the enlistment of Hom Wing, a New York laundryman born in San Francisco, cynically opined, "Chinaman will probably iron officers' shirts.." It described his attire as "strictly Celestial" with slippers "snugly fitting his small feet."

A Pittsburgh paper made fun of Charles Gow, a Chinaman who was born in Philadelphia and son of a laundryman, describing him as sans 'cue', silk pajama trousers, and chop suey dialect. Gow, described as an "embryo soldier," said he enlisted for "the love of my adopted country."

A sense of patriotism motivated Chinese to volunteer. Thomas Moy of Chicago who enlisted in 1917 noted "I am an American as much as any one."

In Selma, Alabama, Sam Loo who was not a citizen wanted to join the Army to represent Alabama to fight for freedom in France in WWI in 1917. It appears that military service was not required of noncitizens because Loo waived his exemption from military service.

Despite the strong desire of many Chinese to join the Army to be patriotic, Chinese were not welcomed and faced barriers. In 1918, Harold Thoung, grandson of a Chinaman and a laundryman in New Jersey, was denied the opportunity to enlist in the Navy because the recruiter felt that he “looked like a Chinaman.”

Even Sing Kee, a decorated WWI hero receiving a Purple Heart and France’s Croix de Guerre for valor, did not receive full respect in the newspaper stories about him.

As an afterthought, one wonders why newspapers of this period bothered to report whenever a "Chinaman" joined the Army. Was it newsworthy because journalists could include condescending side commentary highlighting their "Chineseness?" And, did all enlistees, or just the Chinese, get so much coverage?

No comments:

Post a Comment