About Me

After a career of over 40 years as an academic psychologist, I started a new career as a public historian of Chinese American history that led to five Yin & Yang Press books and over 100 book talks about the lives of early Chinese immigrants and their families operating laundries, restaurants, and grocery stores. This blog contains more research of interest to supplement my books.

12/23/17

Guide to Survival English for Chinese Immigrants

New Chinese immigrants who knew little or no English were at a great disadvantage in everyday business and social interactions. One approach to helping them was to publish common phrases or expressions in Chinese along with the English equivalents. One example is "An ANglo-Chinese General Conversation and Classified Phrases" book by Yee Shu-Nam published in San Francisco by the Service Supply Company. It bears no date of publication but probably it was published in the early 20th century. This well-intentioned phrasebook was of dubious value as any user of the guide would probably have difficulty searching through it for the appropriate expression quickly and it could only cover a very limited number of situations.

Take for example, the scenario below which presents a hypothetical dialogue between a non Chinese speaking customer in a Chinese restaurant and the Chinese manager when the patron received pork chops when he had ordered chop suey!

12/6/17

"Poster Boy" for Angel Island Chinese Detainees: The Complex File of Jeong Hop

Chinese immigrants entering the U. S. on the west coast between 1910 and 1940 were detained for quarantine at the Angel Island Immigration Station, where they also underwent intensive interrogations to determine if they were eligible for admission. Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was in effect from 1882 to 1943, laborers were inadmissible whereas it allowed merchants and their family members to enter if they could provide documents and answer questions about their family and living conditions in their home villages in China. Chinese devised the "paper son" (or paper daughter) method by which a laborer might purchase the identity papers of someone, most times a fictitious person eligible to enter.

As

an interesting aside, he may have been one of the last Chinese to leave

Angel Island because the facility was closed on November 5, 1940, they processed subsequent immigrants at a location in San Francisco. So, we still do not know the name and fate of the 1923 "poster boy."

As a consolation, I decided to see what I could find out more about Jeong Hop's case and what happened in his application. I struck gold when I found an interview in 2006 that focused on his memory of his experiences at Angel Island.

The following excerpt of his interview when Jeong Hop was 76 years old shows how complicated family relationships were for some Chinese immigrants who had to use fake names on their false documents.

How did knowing he was using a false name affect Jeong Hop in how they felt about the deception?

Jeong Hop remembers very little about his life in the Angel Island Immigration Station. Being only 10 years old, he was adaptable and didn't realize that he was being mistreated. He had no strong expectations aside from knowing that he had to memorize all the family members and their relationship to him and to destroy his 'cheat notes' before he arrived in San Francisco on the President SS Coolidge in 1940.

In the mid-1950s when the U. S. offered a Confession Program, aimed to stop the use of the paper son entry method, which allowed Chinese to reclaim their real family surnames without penalty. Jeong Hop gave a detailed account of how this affected his relatives.

Jeong Hop pointed out to the interviewer that he actually was already a citizen before he came over because he was the son of a son of a citizen!

He did have strong feelings about the need for his children and grandchildren to know the history of Chinese in America, especially the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which forced Chinese men to live in a "bachelor society" for decades.

The above photograph of a young Chinese, probably no more than 12 years old and wearing slippers and an ill-fitting suit is the only photograph I have ever seen of an actual interrogation. It is used in many articles about Angel Island Chinese immigration.

The anxiety that this "poster boy" must have felt during this ordeal must have been overwhelming because one false answer and he might be denied entry and deported. Since my parents both underwent these detailed and lengthy interrogations, I cringe seeing this photograph as I can imagine that they must have been in the same situation have to face the Immigration officer, a guard, and a transcriber. This young boy must have been able to speak English because there was no translator in the room.

But who was this boy and was he a "paper son" pretending to be someone else or was he the actual son of a merchant? Did he gain admission or was he deported? If admitted, where did he live, work, and die?

The December 2017 Angel Island Newsletter included an announcement of a forthcoming 2018 documentary, Chinese Exclusion Act, by Ric Burns and Li-Shin Yu that describes the paper son method in vivid detail. My attention was drawn to the announcement that was illustrated with a copy of the Identity Certificate of Jeong Hop, a 10-year-old who arrived at Angel Island claiming to be the "son of a son of a native."

At

first glance of the photo, due to his youthfulness, I wondered if he

might possibly the same boy in the 1923 interrogation photo. That would be a very long shot if it were true. However,

the certificate showed that Jeong Hop did not arrive at Angel Island

until September, 27, 1940 and he was detained for 2 months until Nov. 25,

1940 when he was admitted.

As a consolation, I decided to see what I could find out more about Jeong Hop's case and what happened in his application. I struck gold when I found an interview in 2006 that focused on his memory of his experiences at Angel Island.

The following excerpt of his interview when Jeong Hop was 76 years old shows how complicated family relationships were for some Chinese immigrants who had to use fake names on their false documents.

How did knowing he was using a false name affect Jeong Hop in how they felt about the deception?

Jeong Hop remembers very little about his life in the Angel Island Immigration Station. Being only 10 years old, he was adaptable and didn't realize that he was being mistreated. He had no strong expectations aside from knowing that he had to memorize all the family members and their relationship to him and to destroy his 'cheat notes' before he arrived in San Francisco on the President SS Coolidge in 1940.

In the mid-1950s when the U. S. offered a Confession Program, aimed to stop the use of the paper son entry method, which allowed Chinese to reclaim their real family surnames without penalty. Jeong Hop gave a detailed account of how this affected his relatives.

Jeong Hop pointed out to the interviewer that he actually was already a citizen before he came over because he was the son of a son of a citizen!

He did have strong feelings about the need for his children and grandchildren to know the history of Chinese in America, especially the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which forced Chinese men to live in a "bachelor society" for decades.

Yes, yes, but the relationship is true, so ah... the name is again as I said the same. My

grandfather--. Out of the nine children that he has, every member...of...one of them, and

one of the nine is my true uncle, he came over here to San Francisco. And another one is

my father, he tried coming over. And he did. He was on Angel Island and he passed oral

interrogation, but the paper says when he came over was that he’s supposed to be about

in his twenties, but he was actually in his THIRTIES. So the immigration look at him and

they think he’s much older than he looks, so they got doctors to examine his physical

body and said, “this person is in his THIRTIES.” And my father, through--my

grandfather, through his attorney, got another doctor, who said this guy is in his twenties.

But the immigration won out and so after a stay in Angel Island for about a year, he was

rejected. So again –again my real father, and since he was rejected, I could not come as a

son because he’s ah...he’s not a citizen. So I took them ah... as son of one of the other

nine children. And at that time in 1940, as we were coming, my grandfather went back to

China about in 1938 to bring my brother and I –my brother’s a year younger thac things you brought wit

10/2/17

Chinese American History Mural by James Leong

James Leong, (1929-2011) an internationally known Chinese American artist, was commissioned in 1952 to paint a mural depicting 100 years of the history of Chinese in America to be placed on a wall in the new federally-funded Ping Yuen housing project for low-income Chinese in the heart of San Francisco Chinatown. Starting on the left side of the 5 x 17.5 foot mural, he depicted Chinese immigrant farmers against the background of the Great Wall as they departed to California, leaving their wives and children, to mine for gold and work on building railroads, followed by sections with iconic Chinese concepts, such as a Lion dance during Chinese New Year, image of Chinese women who later came to the U.S., a WW II Chinese American soldier in front of a display of awarded combat ribbons standing atop crumbled papers to symbolize the option to drop "paper names," an image of a Chinese couple and child assimilated to American clothing and lifestyle, with the new Ping Yuen housing facility in Chinatown on the far right. Some traditional Chinese images such as a dragon, pagodas, and a woman wearing a cheongsam are mixed in American attire such as a business suit and tie for a man.

Unfortunately, his vibrant colored mural was a controversial work, rejected because some Chinese felt it was "Uncle Tom-ish" or disliked the image of a Chinese wearing a pigtail or queue. Furthermore, the 1950s were a time of tense relations between Communist China and the U.S. and the American government thought the mural might have symbolism with political undertones.

Leong was disappointed, and went to Europe to continue as an artist for decades in Norway as well as in Italy, before returning to the U.S. and living in Seattle where he felt more accepted than in San Francisco where he was born. One Hundred Years of History remained at the Ping Yuen housing, not hanging on a wall in honor, but neglected and placed unceremoniously in a recreation room where children inadvertently spilled soda and food on it or hit it with misdirected ping pong balls. Finally, in the late 1990s it was salvaged by the Chinese Historical Society of America and painstakingly restored by Leong in 2000, as he describes in the video below, and proudly hung on the wall in the Museum Learning Center since 2001.

8/3/17

The Ships That Brought Early Chinese to Gold Mountain

By 1867, the Pacific Mail Company was given authority by the U. S. government to operate steamships that transported the early generations of Chinese immigrants from Guangdong from Hong Kong to Pacific ports like San Francisco. These were large vessels, some with luxurious accommodations and amenities for cabin passengers.

Chinese could not occupy the upper cabin levels but traveled in the cheaper steerage class below the cabin levels next to the cargo hold, which was crowded, uncomfortable, and unsanitary, especially since the voyage could take several weeks for the earliest immigrants in the late 19th century.

The Pacific Mail Company had financial difficulties by 1900 and the government transferred the route to the Dollar Steamship Lines.

From the early 1900s to the early 1930s, the Dollar Steamship Line, named for the owner, Robert Dollar, operated the President line of ships, President Harrison, President Cleveland, President Wilson, and eight other ships named after Presidents. The success of the company ended with the Great Depression when the high costs of new ships, President Coolidge and President Hoover, proved its undoing, and the U. S. government transferred its ownership and operation to the American President Lines.

Unlike the austere quarters for steerage passengers like our Chinese ancestors, the upper deck cabins of these ships were refined, if not luxurious, as the following images show.

For other photos and descriptions of life on the ship for tourists, this link goes to an archive on the Dollar Steamship Line.

And while it is not stated what Chinese, and other passengers, in the crowded steerage section were provided by way of food, it was probably of poor quality, quantity, and taste.

In contrast, the tourists in the cabin class had dining room service with elegant menu offerings as shown in the menu below on President Hoover in 1932 with the artistic cover.

Among the luncheon offerings were filet of rock cod, fricassee of lamb with dumplings, braised sirloin tips a la Jardiniere, and assorted pastries and cheeses for dessert.

At the top of the menu page is a picture of two Chinese, one giving a fortune reading to the other man, an activity quite unrelated to the meal, but probably included to introduce the white diners to an unfamiliar exotic aspect of Orientals.

It is interesting also to see some of the 1940s advertising used by the American President Lines. So, while the cabin class tourists are wining, dining, and having fun, down below them are the Chinese immigrants stuffed in the steerage class on their way to Angel Island Immigration Station or to other immigration detention centers, hoping to enter Gold Mountain.

7/28/17

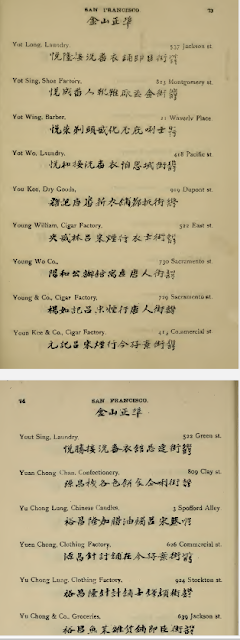

Chinese Business Directory excerpts 1882

Well Fargo Bank published a directory of Chinese businesses in the west as early as 1882. Excerpts of some of the listings are shown here from San Francisco, Oakland, Stockton, Sacramento, Marysville, Virginia City in northern California and Los Angeles in southern California. Also included are businesses in Portland, Oregon and Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

Even from this small sample, it is clear that laundries were the primary business for the Chinese followed by restaurants. Merchants, cigar makers, and shoe makers, were also common.

6/25/17

White Writer Finds 1909 NY Chinatown Not As Bad As Its Reputation

An adventuresome white writer ventured into New York City Chinatown in 1909 to report on life in this enclave. He noted that, "Mention Chinatown and Chinaman and what picture comes before your mental vision? A laundry __ an opium joint __ a chop suey restaurant or a mission where Chinamen become Christians through the efforts of zealous American females and __occasionally some happening that stirs up all the newspapers and public to a passing interest. Rather a gloomy picture if taken as a complete view of the Chinese."

He braced himself before making his visit, writing in the third person, "It was quite natural that one should feel some trepidation in visiting Chinatown for the first time so the writer went there equipped with a letter from the police department but there was no need of any precaution for he was met everywhere with courtesy and hospitality."

The writer concluded after his visit to Chinatown that: “If you go to Chinatown looking for bad things you will find

them—so you will on Fifth avenue or any other locality. If you expect to find

some things uniquely bad you will be disappointed but if you go there to learn

something of interest of a strange people , of a great empire in the far East,

you will do so.”

6/24/17

Podcasting Asian America

A wealth of information about important topics ranging from historical to psychological to cultural aspects of Chinese- and other Asian Americans is available through interviews and discussions on many podcasts, freely downloadable, from itunes.

One podcast New Books in Asian American Studies features interviews of academic authors of important recent books on Asian Americans.

Another podcast, They Call Us Bruce, by Jeff Yang and Phil Yu features discussions and interviews of the work of contemporary artists, politicians, writers, and performers.

Another podcast resource is the Potluck Podcast Collective

3/29/17

The Chinese Are Coming, The Chinese Are Coming (1870)

In 1870, there were few Chinese in the midsections of the United States, but with the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad at Promontory Point, Utah in 1869, the Chinese who helped build the Central Pacific Railroad portion were suddenly out of work. However, their reputation as cheap, and diligent, workers led labor contractors to recruit them to work on building regional railroads such as the Houston Central Railroad in Texas. The newspaper account on January 5, 1870 reported that 230 "Chinamen" had arrived at St. Louis en route to Calvert,Texas. The account noted that if they worked out well, more Chinese would be recruited. It was optimistic that they would hasten the railroad construction after which they would be sent to Kansas, presumably for other railroad work.

After only a few months, the Times-Picayune in New Orleans reported on April 10, 1870, that the experiment with Chinese railroad workers was a "decided success," concluding "Steady at their work, industrious when the contract hours of labor have expired, sober, frugal, willing, and mindful of the stipulations of their agreement, but exacting in the fulfillment of those in their favor, is the sum of the evidence..."

2/28/17

Did Pearl Harbor Speed Up the 1943 Repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act?

One of the greatest injustices in American history involved people of Chinese descent. In 1882, motivated by fear of loss of jobs for whites and by anti-Chinese racism, Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, the only law that singled out a specific ethic group, prohibiting the entry of Chinese laborers for 10 years, but it was extended several times until it was finally repealed after 61 years on Dec. 17, 1943 by President Roosevelt. In signing the bill, Roosevelt proclaimed in a letter to Congress that the Chinese Exclusion Act had been "an historic mistake" and that repeal was "important in the cause of winning the war and establishing a secure peace." However, there was no explanation provided about why after 61 years, the mistake was finally recognized and corrected.

What factors led to the long overdue repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act? In the 1940s, negative public attitudes toward Chinese still existed. Chinese were still seen in terms of outdated negative stereotypes and treated as second class residents. Why would the U. S.government after 61 years choose to repeal this law? Did it finally recognize its gross unfairness? That reason seems unlikely as other injustices by the U. S. government continued such as the February 19, 1942 Executive Order 9066 following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 that authorized the relocation and internment of U. S. citizens and residents of Japanese ancestry to areas remote from the West coast and major cities on unfounded fears that Japanese Americans would sympathize with Japan and be a security risk.

Was it a response to active campaigns by Chinese Americans for repeal? Although Chinese American organizations fought for repeal, and in 1905 helped fund the efforts in China to boycott American goods and products in protest against how Chinese were mistreated in the United States, they failed to overturn the exclusion law. They lacked a powerful leader such as a Martin Luther King who led the fight for civil rights for black Americans in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1940s, Chinese Americans had insufficient influence and political power, given the small size of the Chinese population and failure of the general public to oppose Chinese exclusion, to demand its repeal.

It seems more plausible that the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act was motivated primarily by the World War II conflict between Japan and the United States. Japan wanted to dissuade China from joining the United States against it. Japan continually reminded China that the U. S. had unfairly excluded Chinese from entering the U. S. since 1882 in the hope that China would not join the U. S. against Japan in WWII. Recognition of this situation gave the U. S. Congress a strong incentive to repeal Chinese Exclusion to eliminate this powerful argument of Japan.

Arguments in the House of Representatives deliberations on H. R. 3070 in 1943 show this pragmatic reason was a major justification for repeal. It was recognized that China was a needed ally against Japan and that it was embarrassing to continue the exclusion law against Chinese. Some Congressmen who reluctantly voted for repeal still defended the original 1882 basis for exclusion, namely to prevent 'hordes of Chinese' coming and taking jobs from whites, but recognized that this threat no longer existed in the 1940s so that exclusion was no longer needed. One of the opponents of repeal, Compton White (Dem-IA), defended the 1882 law and argued against repeal because Chinese "coolies" would spread the opium habit among American boys and girls.

Congress set a quota of Chinese allowed to enter using formulas created by the 1924 Immigration Act based on country of origin. The result was that the total annual quota for Chinese immigrants to the United States (calculated as a percentage of the total population of people of Chinese origin living in the United States in 1920) would be only 105. Not only was this number pitifully small, Congress counted Chinese coming from any country, not just China, in the 105 due to fear that much larger numbers of Chinese could enter the U. S. because immigration within the Western Hemisphere was not regulated by the quota system. Thus, if Chinese in Hong Kong, for example, were to apply under the huge, largely unused British quota, thousands more Chinese than 105 could be eligible to enter each year.

Repeal of exclusion had a positive impact on Chinese in America that can not be overestimated. It enabled family reunification, the formation of new families, and gave them the right to become citizens and obtain the right to vote.

But for non-Chinese, repeal of exclusion must have been a relatively insignificant event judging by the low interest shown by newspaper coverage in the days immediately following the repeal on Dec. 17, 1943. Newspaper coverage in the days just after passage of repeal was brief, and usually buried among want ads, movie ads, and comic strips rather than on the front page as shown below.

What factors led to the long overdue repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act? In the 1940s, negative public attitudes toward Chinese still existed. Chinese were still seen in terms of outdated negative stereotypes and treated as second class residents. Why would the U. S.government after 61 years choose to repeal this law? Did it finally recognize its gross unfairness? That reason seems unlikely as other injustices by the U. S. government continued such as the February 19, 1942 Executive Order 9066 following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 that authorized the relocation and internment of U. S. citizens and residents of Japanese ancestry to areas remote from the West coast and major cities on unfounded fears that Japanese Americans would sympathize with Japan and be a security risk.

Was it a response to active campaigns by Chinese Americans for repeal? Although Chinese American organizations fought for repeal, and in 1905 helped fund the efforts in China to boycott American goods and products in protest against how Chinese were mistreated in the United States, they failed to overturn the exclusion law. They lacked a powerful leader such as a Martin Luther King who led the fight for civil rights for black Americans in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1940s, Chinese Americans had insufficient influence and political power, given the small size of the Chinese population and failure of the general public to oppose Chinese exclusion, to demand its repeal.

It seems more plausible that the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act was motivated primarily by the World War II conflict between Japan and the United States. Japan wanted to dissuade China from joining the United States against it. Japan continually reminded China that the U. S. had unfairly excluded Chinese from entering the U. S. since 1882 in the hope that China would not join the U. S. against Japan in WWII. Recognition of this situation gave the U. S. Congress a strong incentive to repeal Chinese Exclusion to eliminate this powerful argument of Japan.

Arguments in the House of Representatives deliberations on H. R. 3070 in 1943 show this pragmatic reason was a major justification for repeal. It was recognized that China was a needed ally against Japan and that it was embarrassing to continue the exclusion law against Chinese. Some Congressmen who reluctantly voted for repeal still defended the original 1882 basis for exclusion, namely to prevent 'hordes of Chinese' coming and taking jobs from whites, but recognized that this threat no longer existed in the 1940s so that exclusion was no longer needed. One of the opponents of repeal, Compton White (Dem-IA), defended the 1882 law and argued against repeal because Chinese "coolies" would spread the opium habit among American boys and girls.

Congress set a quota of Chinese allowed to enter using formulas created by the 1924 Immigration Act based on country of origin. The result was that the total annual quota for Chinese immigrants to the United States (calculated as a percentage of the total population of people of Chinese origin living in the United States in 1920) would be only 105. Not only was this number pitifully small, Congress counted Chinese coming from any country, not just China, in the 105 due to fear that much larger numbers of Chinese could enter the U. S. because immigration within the Western Hemisphere was not regulated by the quota system. Thus, if Chinese in Hong Kong, for example, were to apply under the huge, largely unused British quota, thousands more Chinese than 105 could be eligible to enter each year.

Repeal of exclusion had a positive impact on Chinese in America that can not be overestimated. It enabled family reunification, the formation of new families, and gave them the right to become citizens and obtain the right to vote.

But for non-Chinese, repeal of exclusion must have been a relatively insignificant event judging by the low interest shown by newspaper coverage in the days immediately following the repeal on Dec. 17, 1943. Newspaper coverage in the days just after passage of repeal was brief, and usually buried among want ads, movie ads, and comic strips rather than on the front page as shown below.

2/22/17

A White Aristocrat's Negative View of Delta Chinese in 1941

The Chinese were a small but vital community spread across the Mississippi Delta for over a century operating family-run grocery stores that primarily served the black plantation workers who were not usually welcome at large white grocery stores. Overcoming many obstacles, including racial prejudices, they succeeded and made valuable contributions to their community. Recognition of the Chinese role was demonstrated in an earlier post on this blog in 2011 that presented Mississippi Public Radio interviews with three Delta Chinese with a grocery store background.

However, even as late as 1941, the Chinese "got no respect" from white gentry as illustrated by the demeaning comment about the lack of useful contributions to the community by the Chinese. This observation was made by a prominent white writer and plantation owner, William Alexander Percy, in his nostalgic memoir, "Lanterns on the Levee", which was a romanticized lamentation for "the good old days." However, Percy was not a "redneck" racist; in fact he led the fight against the rising power of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.

The following paragraph excerpted from Percy's memoir provides a clearer context for understanding how even educated and influential white community leaders had a narrow view of Chinese, portraying them as lawless illegal immigrants who often fought among themselves in tong wars.

2/15/17

An Unsung Hero Championed Delta Chinese Right to Attend White School

A previous post on this blog described the legal proceedings in the1920s case in which two daughters of a Mississippi Delta Chinese grocer, Jue Gong and his wife, Katherine, were removed from attending a white school in Rosedale in 1924 because Chinese were not considered caucasian. The school board was sued with a writ of mandamus to reinstate the two daughters in school on grounds of the 14th Amendment calling for equal protection. The school board reversed its decision but it was promptly overruled by the Mississippi Supreme Court. The parents obtained legal assistance and appealed the decision all the way to the U. S. Supreme Court in 1927, but to no avail, as it upheld the lower court.

Most accounts of this case of school segregation of Chinese in Mississippi have dealt only with the legal issues and proceedings, but a new book, Water Tossing Boulders, by journalist Adrienne Berard provides a richly detailed description of the social and cultural context of the Mississippi Delta in the 1920s. This well-researched study brings the people and the community to life as Berard researched the background to set the stage and analyze the complex interplay between racial discrimination against blacks, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, the forced labor of black convicts to build levees, the floods that destroyed the cotton crop that was a mainstay of the Delta economy, how Chinese came to settle in the Delta as early as the 1870s, the intermediary status of Chinese grocery families placing them between blacks and whites, and the mass exodus of blacks from the Delta to the north to escape racism and find employment. Her book, which reads like a novel at times, makes you feel as if you were right there observing events as they unfolded from 1924-1927.

Given the economic disaster in the Delta, everyone suffered. Chinese grocers, dependent on black cotton plantation workers, lost customers in the downturn who could not afford to pay for food. One wonders, then, how Jeu Gong and Katherine were able to pay a lawyer to file a lawsuit. In fact, they could not afford to pay, but they found an unsung hero, Earl Brewer, who rose from a hard scrabble life to become the governor of Mississippi before being soundly defeated later in a bid to become a Senator. Brewer was a progressive who believed the Chinese were unfairly treated and decided to represent them pro bono.

Although the appeal to the U. S. Supreme Court in 1927 failed, probably because Brewer turned the case over to an inexperienced attorney, Berard's book provides us with a better understanding of the many interacting factors affecting race relations in the Delta. Without Brewer's advocacy on the behalf of the Gong Lum family, the case would probably never have been filed.

2/12/17

How To Rid Your Town of Chinamen: Tacoma and Truckee Methods

The "Tacoma Method"

Chinese immigrants arrived in Tacoma, Washington in the 1870s. Many had worked on the Transcontinental Railroad and when it was completed in 1869, they were unemployed but moved to the Pacific Northwest to help build the North Pacific Railroad. Others worked on farms, in fishing, and in saw mills. From their arrival, migrants faced discrimination in a land that was considered by many at the time to be "white only." Anti-Chinese sentiment further increased during the economic depression of the decade of the 1870s.

In Tacoma, anti-Chinese whites adopted an extreme way in 1885 to

deal with Chinese. They simply expelled them from the city overnight.

Chinese were ordered to leave the city

of Tacoma by November 1, 1885 or face being removed by force. About

400 Chinese complied and left their homes and their livelihood out of fear and

intimidation.

On November 3, 1885 several hundred men, led by Mayor Weisbach and other city officials forced the remaining 200 Chinese onto a train bound for Portland. They then burned the Chinese settlements to the ground. Chinese buildings, houses and communities were destroyed in the following days.

This "solution" to the Chinese presence became known as the "Tacoma Method" and was employed in other western communities such as Eureka, California, to forcibly remove their Chinese populations.

On November 3, 1885 several hundred men, led by Mayor Weisbach and other city officials forced the remaining 200 Chinese onto a train bound for Portland. They then burned the Chinese settlements to the ground. Chinese buildings, houses and communities were destroyed in the following days.

This "solution" to the Chinese presence became known as the "Tacoma Method" and was employed in other western communities such as Eureka, California, to forcibly remove their Chinese populations.

For more information about the "Tacoma Method" and to learn about how Tacoma acknowledged the injustice and commemorated its memory with the creation of "Reconciliation Park."

On November 30th, 1993, the Tacoma City Council unanimously approved Resolution No. 32415, which acknowledged that the 1885 Chinese expulsion was “a most reprehensible occurrence,” authorized the construction of a commemorative park located at a former National Guard site on Commencement Bay, and set aside $25,000 for preliminary site plans.[30] The park is a 3.9-acre shoreline plot located at 1741 N. Schuster Parkway in Tacoma, within a half-mile of the site of Little Canton, where many Chinese residents of Tacoma lived before they were expelled in 1885.[31] The park, which officially opened in 2011, currently includes a waterfront trail, a bridge with a Chinese motif, and a pavilion donated by Tacoma’s sister city, Fuzhou, China.

The "Truckee Method"

When the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, about 1,400 now out-of-work Chinese laborers went to Truckee to seek new jobs building railroads through the Sierra Nevada mountains. Within a period of a few months, one third of Truckee's population was Chinese which led to some white men forming a vigilante committee called the Caucasian League. In June, 1876, a small group of white men attacked several Chinese woodcutters outside of town. They set fire to the woodcutters' cabins, and when the Chinese ran out the attackers shot and wounded several of them. One of the Chinese men died the next day. Seven men were arrested and stood trial, but in spite of direct testimony by two of the defendants against the other five all were acquitted after the jury deliberated for just nine minutes.

A Second Truckee Chinatown Across the River

Little more than a year after moving

fire once again raged through the new Chinatown, destroying half of the newly

built homes and stores. There is no record of any loss of life due to

the fire, but again the Chinese were forced to rebuild their community.

Frustrated by the resilience and perseverance of the Chinese, in 1885 Charles McGlashan formed the Truckee Anti-Chinese Boycotting Committee which adopted the following resolution: "We recognize the Chinese as an unmitigated curse to the Pacific Coast and a direct threat to the bread and butter of the working class."

They further resolved that all merchants in town should boycott any Chinese who comes to them either for employment or for goods, in hopes of literally starving the Chinese out of Truckee.

Over the first two months of 1886, McGlashan and other town leaders succeeded in getting every business in town to refuse to sell anything to the Chinese. As food and other supplies dwindled in their community, many Chinese had no other recourse than to leave town. By the end of February the "Truckee Method" of forcing the Chinese away was declared a success by its leaders. However, records indicate that although the boycott leaders claimed to have rid the town of Chinese, a small group remained.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)