Early Chinese immigrants worked long hours on farms, in laundries,

restaurants, and grocery stores, generally with meager amounts of food to eat. Observers were curious about the characteristics of the Chinese diet that enabled them to survive their long labors, and wanted to determine if it was a nutritious and

healthy fare.

In 1900,

Professor Myer E. Jaffa, a highly respected chemist who was the first professor of nutrition

at the University of California in Berkeley undertook a research study

to measure what a sample of 12 Chinese workers ate over 18 consecutive days.

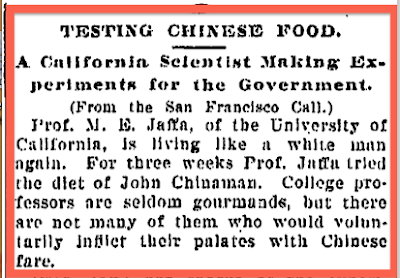

A newspaper account of the research reported in the San Francisco Call began with derogatory insinuations about the palatability of Chinese food.

The study compared three groups of Chinese, professionals, laundrymen, and gardeners, based on the

extent of physical labor involved with their occupations, as noted by the

reporter.

The article summarized some of the findings but only after

first making light of one Chinese who was suspicious initially that the study was a

veiled attempt to tax him for the amount of food he ate. The reporter also described the types

of food that laborers ate as things that “sound strange to the Caucasian ear,

and taste stranger yet to his palate.”

The reported finished with Prof. Jaffa’s findings that the total

protein each day was low, as the Chinese had little meat and relied on a low-fat diet. He felt that their diet

had “an ample amount of nutrition.”

M. E. Jaffa, "Nutrition

Investigations Among Fruitarians and Chinese at the California Agricultural

Éxperiment Station, 1899-1901," U.S.D.A. Office

of Experiment Stations, Bulletin No. 107,

Washington, DC, 1901.

No comments:

Post a Comment