Bret Harte, a popular short story writer during the Gold Rush in northern Californias, wrote a poem, Plain Language from Truthful James, in 1870, which later became more widely known as The Heathen Chinee. In brief, the poem describes how two white miners cheat a Chinese, Ah Sin, in a card game but the crafty Ah Sin outcheats them. But they discover his cheating and exclaim "we are ruined by cheap Chinese labor," and then proceed to pummel the hapless Ah Sin.

As noted in a previous post on this blog,

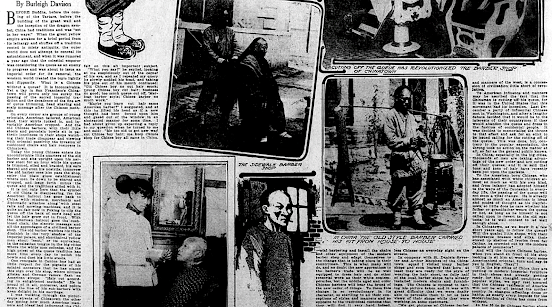

Bret Harte's personal attitude toward the plight of Chinese immigrants actually was sympathetic even though his poem might suggest otherwise. The intent of the poem was to make a satirical commentary on the hypocrisy of whites who cheated the Chinese but then attacked them for the same behavior. Harte's goal failed as his poem intensified this negative image of all Chinese that was in keeping with the national animosity against cheap Chinese labor that led to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, not too long after the poem was published. The image of the heathen Chinee created by Harte's poem quickly became a popular term of derision of Chinese and reprinted in newspapers across the country even as late as the 1920s, half a century later.

A few years later, Harte wrote a less influential poem with a provocative title, "The Latest Chinese Outrage," designed to arouse curiosity about what terrible misdeed the Chinamen committed.

This poem described a confrontation in which "Chinee," 400 of them actually, give some ruffian white miners a taste of their own medicine after they repeatedly failed to pay their laundry bills. Led by Ah Sin, they take the livestock and possessions of the miners as payment.

When out of the din

To the front comes a-rockin' that heathen, Ah Sin!

"You owe flowty dollee--me washee you camp,

You catchee my washee--me catchee no stamp;

One dollar hap dozen, me no catchee yet,

Now that flowty dollee--no hab?--how can get?

Me catchee you piggee--me sellee for cash,

It catchee me licee--you catchee no 'hash;'

Me belly good Sheliff--me lebbee when can,

Me allee same halp pin as Melican man!

The Chinese capture one miner, Joe Johnson, and force him to ingest opium, shaved his eyebrows, tacked on a cue (queue), dressed him in Chinese clothing, painted his face with a coppery hue, and stuffed him in a bamboo cage on which they placed a label that read "A white man is here" and left him hanging like ripening fruit.

And as we drew near,

In anger and fear,

Bound hand and foot, Johnson

Looked down with a leer!

In his mouth was an opium pipe--which was why

He leered at us so with a drunken-like eye!

They had shaved off his eyebrows, and tacked on a cue,

They had painted his face of a coppery hue,

And rigged him all up in a heathenish suit,

Then softly departed, each man with his "loot."

Yes, every galoot,

And Ah Sin, to boot,

Had left him there hanging

Like ripening fruit.

One wonders whether Harte, in writing this poem, was trying to make amends for all the harm his "heathen Chinee" character, Ah Sin, created for the Chinese. It would be unlikely that many if any, Chinese would have read the poem, but if they did, they might feel some vicarious vengeance. On the other hand, anti-Chinese whites might experience anger if they read it. Unlike Plain Language from Truthful James, it had little impact on white-Chinese relations.