The vast majority of immigrants who came from China in search of gold in California starting in 1848 and during the 1860s to work on the construction of the western part of the transcontinental railroad were primarily young men. Most were not married, or if they were, did not bring their wives because they hoped to return to China after they made enough money.

In 1870, there were approximately 58,000 Chinese men and about 4,000 Chinese women and girls identified in the U.S. Census so it is obvious there were few marriages created between Chinese men and women. Anti-Chinese sentiments, as well as Chinese preferences for marrying a Chinese partner, left these thousands of Chinese without sexual outlets, aside from forming homosexual liaisons, a topic that is understudied as a taboo topic, or patronizing prostitutes. In 1870, about 61 percent of the roughly 4,000 Chinese women in California were prostitutes, according to Ronald Takaki in his landmark 1998 study,

Strangers in A Different Land. It should be noted that most of these women, some actually barely into puberty, and at least one girl 6 years-old, were coerced or involuntary participants controlled by unscrupulous Chinese.

I was startled by this huge statistic. For 4,000 females, 61% would be over 2,400 prostitutes. By the way, their patrons were not limited to Chinese men, as "yellow fever" existed among white men even back in the mid-19th century. I decided to check census listings for Chinese women born in China but living in the U.S. in 1870 whose "occupation" was listed as "prostitute." I should add I saw some towns where the occupation of many women was keeping house" or as "public." I wonder if those were polite terms for "prostitute." ( I also saw one where the census taker wrote "whore" for one woman's occupation).

I found page after page of census records full of prostitutes. Below are 2 pages for San Francisco in 1870. Seeing lists of actual names of these prostitutes, many under the age of 15, was more distressing than looking at statistics.

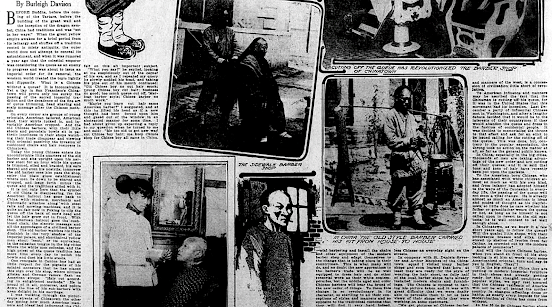

I hasten to add that a place like San Francisco also had many other occupations for Chinese men including cook, peddler, tailor. jeweler, doctor, barber, cigar maker, and of course, laundryman.

In contrast, in small mining towns such as Silver Bow, Montana, most of the Chinese men were miners along with two laundrymen to wash their clothes and a couple of prostitutes to fulfill their carnal needs. (Note that the census taker did not bother recording their names. All men were listed as "Chinaman" and the two prostitutes as "Chinawoman"!

Thankfully, a decade later in the 1880 census, although still unacceptably high, there was a big drop in the percentage, 24, of Chinese women working as prostitutes.

Journalist

Gary Kamiya presented an excellent account summarizing the factors responsible for the high number of Chinese prostitutes and their living conditions in San Francisco in the late 19th century. A more detailed analysis by sociologist Lucie Cheng Hirata “Free, Indentured, Enslaved: Chinese Prostitutes in 19th Century America,” published in the autumn 1979 issue of the journal

Signs can be viewed

at this site.